One of the main challenges faced by cloud customers is how to handle situations where legislation in a cloud vendor’s home country conflicts with legislation in the customer’s country – specifically where a government agency requests access to data stored by a cloud vendor.

Most cloud vendors do not want to share an organisation’s data with governments. Indeed, it is not in their interest to do so since the disclosure of such data could be detrimental to the vendor’s reputation. The challenge lies where the cloud vendor may be legally compelled to release information by their own government, and when the release of that information causes one of their customers to violate their own country’s data protection regulations.

Of course, well-managed organisations are comfortable handling requests for information where criminal activity has been identified whilst simultaneously protecting other unrelated information. This is not, therefore, a question of avoiding such requests: it is a question of how customers can take control of their data, avoid breaching regulations in their own country, and only reveal information related to the subject of such a request.

The question therefore becomes:

“How can we as an organisation retain control of our data such that legal requests are sent to our organisation, rather than the cloud vendor?”

AWS has been securing their customers’ data for many years using strong encryption and their own encryption service – KMS (Key Management Service).

A lesser-known service provided by AWS – CloudHSM (a physical “Hardware Security Module” hosted by AWS and dedicated to a single customer) can be utilised by KMS to store a customer’s encryption keys.

The Hardware (which is FIPS 140-2 Level 3 compliant) underpinning CloudHSM can only be accessed by AWS in two ways:

- To get information about the HSM Device, such as its IP Address, Firmware Version, etc.; and

- To wipe/zero-write the HSM upon customer request.

However, AWS cannot see, access, extract, or in any way manage the customer’s keys. Therefore, on receipt of a request by a law enforcement agency AWS would – when presented with a valid legal request – be able to hand over encrypted data, but not the keys required to unencrypt that data.

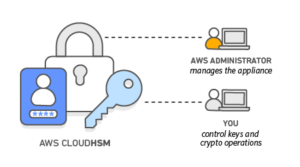

The following illustration from AWS shows this separation of roles:

Naturally, it could be argued that data has still been handed over to a government agency – albeit encrypted data. However, the fastest route for a government agency in this case would be to request the data directly from the organisation instead of the cloud vendor.

It should be noted that storing data in the cloud can provide a number of potential benefits – such as segregation of duties between operations and data centre staff, heavily secured data centres, military-grade data-destruction procedures, integrated encryption, and management planes – that are simply not available in most brick-and-mortar data centres and, indeed, often provide higher levels of security than most organisations can provide themselves.

Using a CloudHSM-backed KMS instance to encrypt your AWS RDS Databases, Volumes, Messages, Buckets, etc. is one of a range of tools that can be used to help secure your data and demonstrates your organisation is taking reasonable measures to secure its data.

(Note that in using CloudHSM the operational responsibility of the keys, the rotation of the keys, and the maintenance of key versions becomes the responsibility of the customer, and not AWS).

The content of this blog post is for informational purposes, and is the opinion of the author; the content does not constitute legal or professional advice. Any action taken as a result of the content of this article are taken at your own risk.